Since the majority of my behavior practice involves working fear and aggression cases, including separation anxiety, I spend a lot of time helping clients navigate how we can break the things their dog is afraid of, whether it’s strangers, absences, noises, dogs or other things, into a version of the problem that isn’t a problem for the dog and one that doesn’t elicit any fear reaction from the dog. This technique, originally developed by behavioral psychologists to treat people with phobias and fears, is called systematic desensitization. It works by breaking the overall bigger problem into little bite sized pieces that the dog can handle. The goal is always to make sure the dog stays “under threshold” – under the point where the dog becomes anxious or afraid. And while it may sound simple to describe, it’s a delicate balancing act, where I’m constantly juggling all the little pieces of the puzzle that make up the dog’s fear issues. I’m making sure the scary thing is far enough away or quiet enough or not moving, so the dog can feel safe, and then we build on that foundation and make it gradually more difficult over time.

Let’s look at how systematic desensitization comes into play with two common issues I deal with in my behavior practice.

First, separation anxiety. Fundamentally, separation anxiety dogs are afraid of being alone. But it’s not that simple – there’s more than just being afraid of being alone. Because dogs are great dot connectors, often dogs with separation anxiety have learned all the little clues that lead up to someone leaving. Some dogs can even tell the difference between sneakers you wear to walk them and work shoes you put on for a full day at the office! There’s many other triggers or “pre-departure cues”, such as showering, putting on shoes, putting a jacket on, picking up keys, pickup a purse, stepping through the door, locking the door, opening the garage door, turning on the car, closing the garage door, backing out of the driveway and driving away that happen before the actual being alone part. And then how long is the dog alone? 5 minutes is a lot different than 6 hours. Before you get to the part where the dog is alone, there’s a lot of things to work through first.

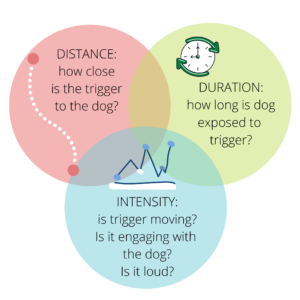

Next, for dogs who are afraid of strangers (or dogs or other more physical or tangible things like trucks or sounds), we set the dog up for success by manipulating various degrees of the scary thing including distance, duration and intensity, to teach the dog that the scary thing can be safe in some reduced form. We move the dog farther away from the stranger, or use a barrier like a door or gate. We make sure the stranger is quiet and not moving, not changing positions, not coming towards the dog, not reaching for the dog and not looking at or engaging with the dog. We reduce the time the dog is around the stranger. And all of these factors can be increased/decreased depending on how the dog is responding and feeling.

Next, for dogs who are afraid of strangers (or dogs or other more physical or tangible things like trucks or sounds), we set the dog up for success by manipulating various degrees of the scary thing including distance, duration and intensity, to teach the dog that the scary thing can be safe in some reduced form. We move the dog farther away from the stranger, or use a barrier like a door or gate. We make sure the stranger is quiet and not moving, not changing positions, not coming towards the dog, not reaching for the dog and not looking at or engaging with the dog. We reduce the time the dog is around the stranger. And all of these factors can be increased/decreased depending on how the dog is responding and feeling.

Again, we break it up into manageable bite sized pieces the dog can handle. With these latter cases, I also bundle desensitization with counterconditioning – a powerful one, two punch, adding food to help create positive associations, and help change the dog’s feeling from worried to yippee, about the scary thing, by feeding at perfectly timed instances (NOT just randomly throwing food around). But counterconditioning is a topic for another blog post!

When using systematic desensitization it’s important to track data and the details of training, so you can look for trends and adjust parameters accordingly – sometimes up, sometimes down. All of my separation anxiety clients have a personalized Google Spreadsheet where all their training assignments are logged, so data can be evaluated and so when there is a a regression (because regressions are normal and to be expected!) that I’m able to look things over and look for patterns or factors that might be contributing to those regressions.

Data is important but even more important is how to interpret that data and knowing how to make criteria decisions on how to move forward. This is what sets apart working on your own and working with a qualified trainer. How to set criteria in training, (always starting at a point where the dog is 100% comfortable, not just tolerating the scary thing), when to adjust that criteria, how to read body language/communication, monitoring for trigger stacking, and when to make things harder, are all critical to success in desensitization. If you bite off more than the dog can chew, you risk sensitizing or flooding the dog, which will set back any training progress you’ve made or could significantly worsen his fears.

While fear is the most difficult thing to improve in a dog, we can work to come up with a plan to help your dog feel safer, so if you and your dog need help, schedule a consult today.

Be sure to check back tomorrow. I’m releasing an exciting separation anxiety resource and can’t wait to share it with you!

Happy training!

![]()